War Narratives/ Girls with gun

This article has been published on the last number of the magazine Leggendaria (www.leggendaria.it)

The question is simple, the answer is not at all. Why the Kurdish fighters are so successful?

Obvious the first observations that come to mind: because they are fighting for independence of their homeland, they are community leaders, they did not hesitate to take up arms to fight. They have become in no time an icon of contemporary, brave in battle as in social media. The world loves them, no harm.

At the same time the iconography of this present time shows many other images of armed women: the young British graduates who join the IS and go to fight in Syria; the military engaged in the armed forces of any country in conflict. In short, all them fighting, killing. And so I try to look at them now, through the images that return the ambivalence of worlds that are not at peace and see many women on the front lines, out of the fiction at this time.

The first that comes to my mind is related to my family history: the woman with black uniform while doing the salute and smile, the chubby cheeks that remained until her death, is my grandmother fascist since her youth, actively engaged in the field, during the war gave to my grandfather my uncle and my mother – still very small – for the office of inspector of the Fascism. She taught women how to descend from the houses on fire using a sheet in the manner of convicts; how to boil water, how to keep healthy children when there was no food. My mother remembers her one time drunk by the gin led by the Americans, in the days of Piazzale Loreto. I remember her as the one who has always taken care of me, who taught me to play cards like every Neapolitan high society could do; I well, now great, feminist and left, questioned on the choice, maybe then for the majority it was the only option. I keep that picture in my room, along with another of the same elderly woman in wig that goes to the airport to welcome her son who emigrated to America.

For an association of ideas which I can not dissolve and always going back, I found a few clicks of 2002: two hundred Chechen terrorists – mostly women – took up a Moscow theatre, demanding the withdrawal of Russian troops from their land. Putin does order the launch of deadly gas in the theatre, wiping out a third of the viewers and more than one hundred Chechen women: look at them today, Cinderella dressed in black, wearing vests packed with explosives that lie like sleeping on red velvet armchairs, because their midnight is long past and there are neither cars nor pumpkins to bring them home.

I force myself to look at things much more despicable for my gaze to the woman, the American soldiers in the maximum security prison of Abu Ghraib in Baghdad, which in 2004 were at the center of an international scandal and accused of torture and abuse of Iraqi prisoners: smiling using their fingers in sign of a victory while posing on a pile of human prisoners with their heads wrapped in plastic bags or while walking on all fours on a leash or even make them bring the pigs, banned by the Muslim religion.

Over ten years after the iconography changes and so the quality of the shots: anyone can portray the present moment, improve technically and offer it to the world in real time. We come to today’s Kurdistan. Not coincidentally around Christmas Day, it circulates a beautiful image: a gorgeous fighter, the long robes, sat on a chair in an empty spartan room. Nursing her child, behind the wall it is supported an AK-47; her skin is rosy and bright, clear eyes, the boy’s shorts is blue like the Madonnas of Antonello da Messina, the laying of the Virgin of Piero della Francesca, “full of grace”, if she had the clothes decorated with pearls would seem the work of Renaissance Cosmé Tura. She fights, is the mother, is Kurdish, it is definitely her moment. As is that of her fellow girls fight, beginning to show both green uniforms or camouflage and rocket launchers, or dance together while holding hands. Still, lying among the flowers in the grass, weapons close at hand, they remember our weeders, Silvana Mangano in Bitter Rice. Obvious that I like them, it could not be otherwise.

At the same time and with the same fascination I am kidnapped by the click of two solvates in Pakistani desert: black abaya that leaves only the eyes uncovered, on their knees, they practice to use the machine gun. In other shots I see the red polish on their nails and somehow it softens me: I know how hard it still can be to women live the military life, but that’s not the point. Those women will shoot to the Taliban or perhaps will join the force to kill the Syrian militants of the IS, where there are also women, the same black suit, dark glasses ultra chic, they read their press death as equally good anchor women.

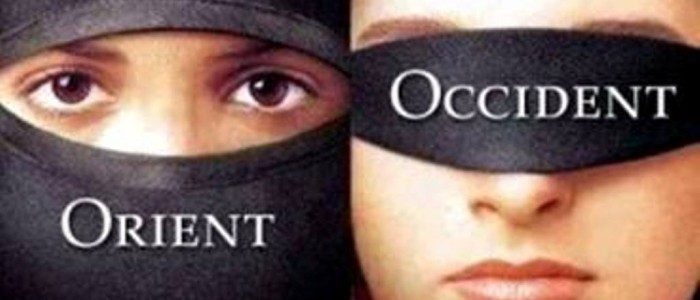

Is it possible to reconcile the wide and strident abacus image of armed women who for various reasons choose to take up arms? Of course not. We like the Kurdish women, smiling and with long braids, but we do not like those in black because they kill for a cause that we do not share. Not surprisingly, the question that arises here is another. If many of us have long been against all forms of violence (and simultaneously) have been fighting at the same time because the women had a decisive role in the armed forces, we knew or perhaps imagined facing such scenarios we would find today? The resolutions of the United Nations for over 15 years ask women to be active engine and agent of change in the peacekeeping operations had perhaps given that today some of the “enemy” have Western passports and that they are acting in an otherwise nasty as engines well of other tragic changes?

What they are the images recall as many snapshots of the doubt and ambivalence that accompanies the present, but above all that call into play the female identity, beyond stereotypes of women as “good” and the “bad” in the iconography of today gallery. There are fighters who are breastfeeding, the students voted to Islam who choose to have for the rest of their life their faces covered and fight the infidels; the old Kurdish holding in his arms a rocket launcher (and who knows how many photos were prepared as needed, in truth, but always they makes its effect); and not least, the beautiful and touching picture of American soldiers who lost their legs in the war fronts and decided to pose as a wonderful post-atomic models with their titanium prosthesis. And the Ecuadorian artists who for the Biennale of Venice in 2015 have chosen to represent themselves with their faces hooded by guerrillas while topless nurse their children.

All of them, all of us have in common belonging to the feminine universe.

“Photos can not create a moral position, but may strengthen it,” wrote Susan Sontag in her essay On Photography. Reality and image in our society. “Pictures can be remember faster moving images … Television is an uninterrupted succession of images, each of which cancels the previous one (…)” It is one thing to suffer, to live with another photographed the emotions of suffering, that does not necessarily strengthen the consciousness or the ability to have compassion. ” In her latest book, Regarding the Pain of others, as she approached the end of her life, Sontag changes radically opinion: “Let the atrocious images haunt the (…) Those images say: this is what human beings are capable of doing, what – enthusiastic and convinced of being right – lends itself to do. Do not forget. ”

So we do not forget. And more than any others we are aware in the present, in which every conflict asks us daily to take sides for or against the shooters for the cause that we feel better or detestable. Pushing us once again, in our lives of women, to reshape the registers of feeling and of interpretation.