War narrative/American sniper

A friend who, like me, has worked in areas of war, told me a few days ago – in the face of mutual impressions of our lives of everyday “normal”, in countries where few people would set foot – that the experience is a little ‘how to be long hospital patients, where after the first few days you get used to a daily rhythm procedures that make sense only in there and that in no time they appear normal, because it is our brain that adapts itself quickly to difficult solutions, extreme, and it looking adjustments useful for survival.

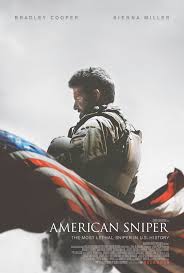

I saw “American Sniper” by Clint Eastwood, and before that I read many positive reviews and not: anti-heroism, too much Americanism, rhetoric, and so on. I was not surprised, the old Clint is American to the core, but I like that patriotism is continually questioned in his films since ten years. See the scenes of the sniper Kyle – as his father taught him – protects the American flock from Fallujah’ (Iraq) terrorists is like to see America today, that questions about what happened and made from September 11 to today.

I saw for the first time American troops in Kabul last summer. I lived and worked in two compound – one was to the United Nations – so closely with people and vehicles. He hit me in the early days, in addition to the deployment of armored vehicles and sandbags, watchtowers and shotguns, the young age of the children with whom at times we shared the common space of the room: no one seemed to have more than 25 years and I I was constantly thinking about their families and anxiety for their distance, especially since there are no images in provisions. Herat or Kabul or Fallujah are not New York and Paris, they are places where civilians come with a dropper, where much is destroyed, and also when there is no curfew yet who can go into the street, to eat, to the market to see the carpets .

From there I was reading the email from my old uncle who lives in America for over 50 years: we are following very closely the recount of the two presidential candidates, he said (I was among those from UNDP team who were recounting). In Italy my friends even knew what I was doing there, they said just please come home.

In “American Sniper” it relives the same feeling: an “idea” of America that has to fight an enemy, a threat that has millions of faces, dozens of cities, which sometimes gives the impression of not understanding too well because it is doing (for themselves, for us, for Christianity?); on the other side there is an idea of Islam that destroyed cities, children carrying bombs, athletic snipers who have put a bounty on the best pull chosen that the US has ever had; sand and dust, and of course enemies.

Within this scenario, there is the “normality” of the soldiers, or in general the work in war areas, where you do not notice it at checkpoints, the infernal heat, the prayer that marks the hours of your day from the mosques. One day it becomes routine: get up, get dressed, eat, shoot, be in constant and close relationship with those who work with you.

And when you come back to home, when you leave the strange hospital, that does not add up: the others do not understand you because there is something you cannot explain, the legend of the heroic soldier of salvation is not your clothes: you stay there , ears ready to minimum hissing, the violent kickback from the attacks of a dog, it is impossible to tell, especially those who love you. The real movie that Clint made is this: it says that to reach home, or take home your brain with your body, sometimes it’s damn hard.